Development of the Plastic Drumhead

Polyester film was invented in England in the 1940s at Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI), as a substitute for the cellulose film used by reconnaissance aircraft during wartime surveillance work. The cellulose film was prone to breaking, which would negate the effort of the mission. After the war, the DuPont Chemical Company bought patent rights to manufacture polyester film in the United States. Their product, called Mylar, was used extensively as a packaging material, for recording tape, and as insulation for electric motors.

The Advent of Mylar Drumheads

Jim Erwin, a chemical engineer for 3M, was the first to use Mylar as a drumhead. "I used to go to New York to see my jazz trumpeter brother play in the nightclubs there," says Erwin. "It was around 1952 or 53, and he was leading a band at the Cafe Metropole. Duke Ellington’s former drummer, Sonny Greer, broke a drumhead that night, and later I went up to him and told him that I thought I could make a head for him that wouldn’t break. I had been working with polyester film at 3M for about eight years and thought it might work as a head material. I went back to Minnesota and made one up by serrating the edge of a piece of Mylar so it could be bent around and attached to the flesh hoop of a calfskin head. I took it back to Sonny in New York, and he used it and said that it was the best head he’d ever played on. He was really impressed with its uniformity." Joe Grolimund, at Selmer, experienced the same, (at roughly the same time as Erwin), as he was also experimenting with various materials for drumheads - Mylar in particular. His head was made by tacking polyester film to a flesh hoop. He suggested to Bill Ludwig that they try to develop the idea, but Bill wasn’t convinced. Nothing happened until Bill found out that someone else was going to show a Mylar head at a trade show. Then, according to Grolimund, "...he got excited and got one together for the show."

Mylar Gains Traction

In late 1953, Remo Belli again went on the road playing drums, this time with movie star Betty Hutton’s show. In Chicago, they had an engagement at the Schubert Theatre. Slingerland, Gretsch, and Ludwig were based out of Chicago at that time, and Frank’s Drum Shop, a highly regarded shop, was also located there. As a touring player, Remo had free time during the day, and he took this opportunity to visit all of these places. Since Remo was a successful touring drummer, and also part owner of Drum City in Hollywood, he was welcomed at Slingerland and the other companies. Bud Slingerland showed Remo a new plastic made by DuPont called Mylar. Remo wished Slingerland luck but had no interest in it. Both Slingerland and Ludwig had some interest in the material at the time.

Challenges and Innovations in Drumhead Design

In early 1956, Remo was preparing Drum City for their annual "Percussion Fair." He obtained a piece of Mylar from C.D Lamorre and stapled it onto a 14” wood flesh hoop for display purposes and became interested in its potential. In late 1956, Marion I. “Chick” Evans completed a Mylar version drumhead that consisted of a drilled outer hoop that tacked a Mylar head to a smaller, inner hoop. He sent out sales letters for the heads, one of which reached Drum City. Remo already knew about Jim Irwin’s experiments, had discussed the Mylar concept with Slingerland and Ludwig when he was on the road years earlier, and had worked with Mylar on his own. Remo made an appointment to visit Chick in Santa Fe, New Mexico as a drummer and a store owner, interested in knowing more about the product as a player or a distributor, not a potential manufacturer. Upon arrival on the designated day and time he found that Chick was living and working in a boarding house and was in total disarray. He found that he did not have an adequate manufacturing facility and that his drumhead design was flawed. Chick’s drumhead was a piece of Mylar tacked to a wooden ring. When Remo saw this head he knew immediately that this design would not work, as he had tried something similar for the Drum City window display, only using staples instead of tacks. While there, Remo never saw Chick’s “factory” in the basement of his boarding house and at one point Chick offered to sell his business to Remo for $5,000, but Remo was not interested after seeing things first hand. Nonetheless, Drum City distributed Evans heads for a while, with Roy Hart (Remo’s partner) using them on session gigs, even with their shortcomings. What Remo and Roy learned was that these heads simply didn’t hold up and could not withstand the tensioning and rigors of being played with sticks. Often the Mylar would tear from the hoops and the film would dent badly. Bill Ludwig: “Both Grolimund and Evans sent us the first Mylar heads we had ever seen tacked…yes, stapled to OUR wood hoops. They were indeed weatherproof and performed well on a drum IF you didn’t over tighten the heads. When this happened, the Mylar simply pulled away from the flesh hoop."

Legal Battles and Patent Issues

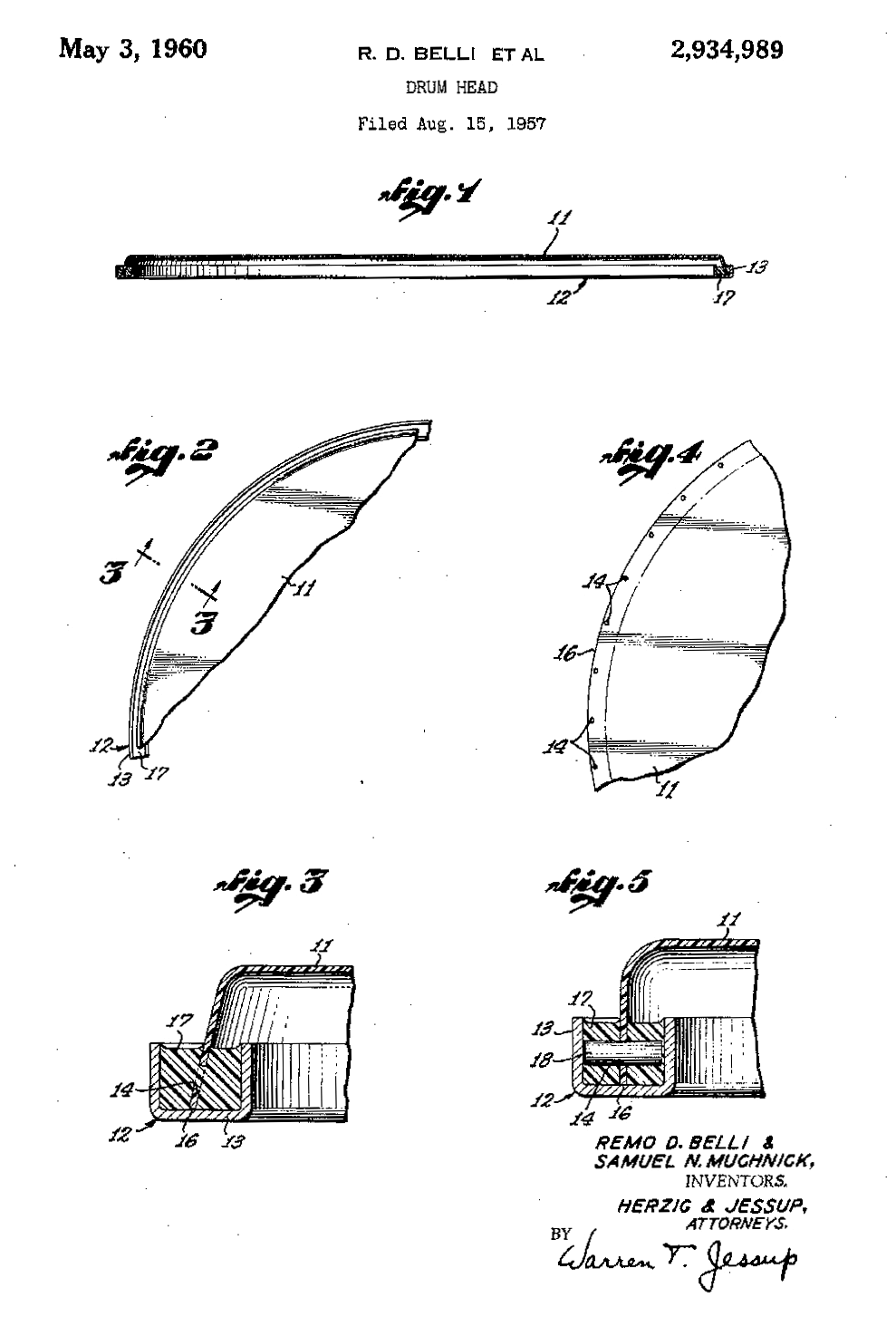

While all of this was happening, Remo met a chemist named Sam Muchnick and together they developed an aluminum channel design filled with resin to anchor the Mylar. Chick soon abandoned the failing tacked version drumhead, in favor of pouring resin into a mold in which the head’s membrane was seated into. When removed from the mold, the hoop was a flexible resin, not the more rigid Remo aluminum channel design. The idea of the Mylar head wasn’t Chick’s, although he self-proclaimed it in his 1964 Mini-catalog "Historical and Present Day Facts" section. Jim Erwin, Jim Grolimund at Selmer, Ludwig, and Slingerland had the idea years before Chick. The idea wasn’t patentable, but the design of the head could be. Remo and Evans drumheads differed significantly, as did Ludwig’s & Slingerland’s. On December 1, 1958, Evans partnered with Bob Beals, Harold Beals, and Larry Drehemer to begin Evans Products, Incorporated, for the purpose of making and selling Evans drumheads. A short time later he sold his share of the business to Beals. Beals continued with the flexible flesh hoop design for years even though it too was flawed, as the flesh hoop simply conforms to an out-of-round drumshell as well as collapsing against the shell OD, which dampens the drumshell. Slingerland and Ludwig later battled lawsuits with each other on their crimped style Mylar drumheads. Interestingly enough, Remo had seen this dry crimped design before Bill Ludwig Sr. from Oscar Bauer in Switzerland, who was making 14” high tension heads for basel drums. Oscar never filed a patent for his design and after watching Oscar make heads Bill came back to the States and filed a patent on the design. This design too had, and still has, its flaws as it does not make a good sounding two ply drumhead. Drumhead patents were first held by Jim Erwin, then by Remo, and then by Ludwig for their unique designs. Remo’s is the one still copied today by all of the major manufactures, using an aluminum hoop filled with resin.

Creation of Remo Inc.

Remo: “We developed the first successful Mylar head, and we were the first ones that had the ability, and the strategy for marketing it. We accommodated or led the market in what they needed, every single step of the way.” In 1956, Drum City’s accountant, Sid Gerwin, introduced Roy and Remo to a chemist he knew, Sam Muchnick. Sam was interested when the plastic drumhead subject came up, and he and Remo began working on a new design for a drumhead. They spent quite an amount of time experimenting and testing. By early 1957 they had developed what proved to be the first successful plastic drumhead design. Remo states that Sam really was the one who had the basic ideas that worked. This process is still what is used today. A Mylar head, (with a shaped, crowned edge and little holes punched out around the perimeter), and a round, metal channel were matched and held together with a liquid adhesive. This was the first version of a Mylar drumhead that didn’t involve tacking the film to a flesh hoop. Remo and Sam Muchnick began their experiments, and by June 1, 1957, Remo, Inc. was created to market the aluminum channel drumheads. Sid Gerwin came up with the name. Remo has never claimed to have made the first synthetic head. Instead, Remo has claimed to have developed the Weather King head, the first successful plastic drum head. In May of 1957, Remo attended the Tri-State Music Festival in Enid, Oklahoma, where he showed the head to Bill Ludwig, among others. Bill said that his company had been trying to create a plastic head as well. Ultimately, Ludwig became one of Remo Inc.’s first OEM customers, with many more to follow, including Slingerland and even AMRAWCO! (the drummer-known calfskin drumhead company).

Cultural Impact and Legacy

“The music world first became aware of the back workshop experiments by Remo in the summer of 1957, at the National Association of Music Manufacturer’s annual show in Chicago, when he prowled the hallways and rooms of the Palmer House Hotel while showing off his new plastic head, which he brashly described as the long sought substitute for calfskin heads. He returned to Los Angeles with orders for 10,000 of them, and Remo, Inc. was in business... Remo, in early 1958, developed a chemical coating (known widely as the Coated Ambassador) which not only made the products come closer to what everyone expected a drum head to look like, but also produced a better sound, superior either to animal or other synthetic heads. The sound was especially noticeable in the greater crispness when brushes were used.” (The Music Trades, February, 1982, “Remo At 25”, Paul A. Majeski). More orders for the Remo Weather King head begun to appear. Because of Remo and Roy Harte’s experience as drummers, their relationships with other drum manufacturers and drum shops, and Drum City’s being a “hub” for local and travelling players, it was not too difficult to gain exposure for the Weatherking. The head created its own momentum.

“Weather King” was Remo. “Weather Master” was Ludwig and “All Weather” was Evans.

Remo coined the King themes: “Diplomat” (to the King), “Ambassador” (to the King), and Emperor (meaning King itself) to denote the thickness of the Mylar.

- Diplomat was 7.5 mil

- Ambassador was 10 mil

- Emperor was two plies of 7.5 mil

These names are still referred to today to denote thickness. The names are even used in competitor catalogs to reference their particular thickness connotations.

Bibliography

- Beck, John. History of Percussion.

- Thompson, Charles “Woody”. “The Mylar Drum Head,” Modern Drummer, August 1989.

- Ludwig, William F. The Making of a Drum Company.

- Belli, Remo. Professional Drum Shop’s 50 Years. DVD.

- Zygmont, Tom. Remo Belli Audio Transcriptions.

- Belli, Remo. “Just for the record,” dictations to his personal secretary, Jackie Stein.

Published:

Aug 13, 2020

Updated:

Sep 18, 2025